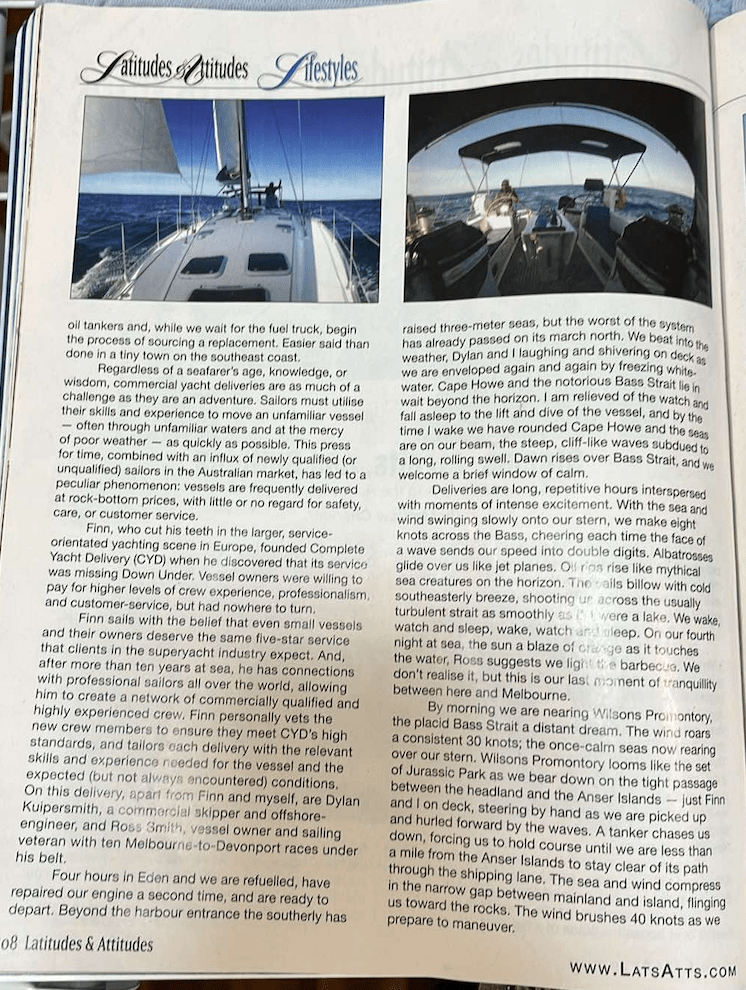

Published in Latitudes & Attitudes, Winter Issue, 2021, pp. 107

The first puff of a southerly hits my face like a promise. I squint into the darkness, spy a wind-line on the water. The termination of the mirrored sea, as abrupt as if it had never existed. The headsail shivers, curls inward and snaps back into shape. I check my watch.

It is 4am. The wind has come early.

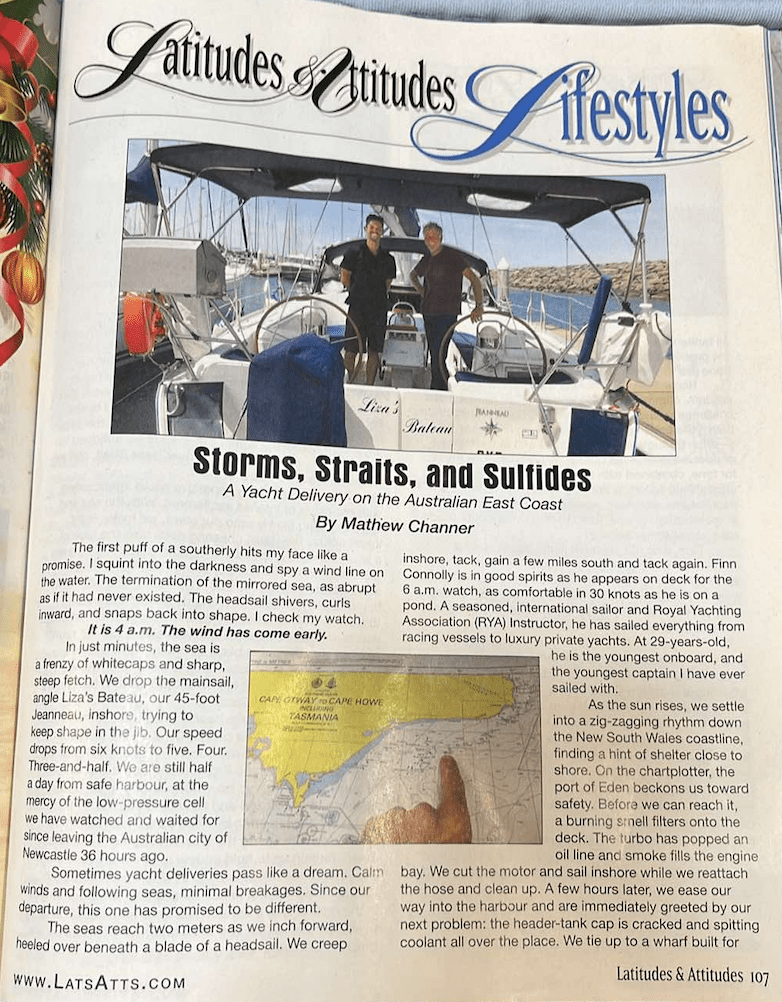

In just minutes, the sea is a frenzy of whitecaps and sharp, steep fetch. We drop the mainsail, angle Liza’s Bateau, our 45-foot Jeanneau, inshore, trying to keep shape in the jib. Our speed drops from six knots to five. Four. Three and half. We are at still half a day from safe harbour, at the mercy of the low-pressure cell we have watched and waited for since leaving the Australian city of Newcastle 36 hours ago.

Sometimes yacht deliveries pass like a dream. Calm winds and following seas, minimal breakages. Since our departure, this one has promised to be different.

The seas reach two meters as we inch forward, heeled over beneath a blade of a headsail. We creep inshore, tack, gain a few miles south and tack again. Finn Connolly is in good spirits as he appears on deck for the 6am watch, as comfortable in 30 knots as he is on a pond. A seasoned, international sailor and Royal Yachting Association (RYA) Instructor, he has sailed everything from racing vessels to luxury private yachts. At 29-years-old, he is the youngest onboard, and the youngest captain I have ever sailed with.

As the sun rises, we settle into zig-zagging rhythm down the New South Wales coastline, finding a hint of shelter close to shore. On the chart-plotter, the port of Eden beckons us toward safety. Before we can reach it, a burning smell filters onto the deck. The turbo has popped an oil line and smoke fills the engine bay. We cut the motor and sail inshore while we re-attach the hose and clean up. A few hours later, we ease our way into the harbour, and are immediately greeted by our next problem: the header-tank cap is cracked and spitting coolant all over the place. We tie up to a wharf built for oil-tankers and, while we wait for the fuel truck, begin the process of sourcing a replacement. Easier said than done in a tiny town on the south-east coast.

Regardless of a seafarer’s age, knowledge or wisdom, commercial yacht deliveries are as much of a challenge as they are an adventure. Sailors must utilise their skills and experience to move an unfamiliar vessel, often through unfamiliar waters and at the mercy of poor weather, as quickly as possible. This press for time, combined with an influx of newly qualified (or unqualified) sailors in the Australian market, has led to a peculiar phenomenon: vessels are frequently delivered at rock-bottom prices, with little or no regard for safety, care, or customer service.

Finn, who cut his teeth in the larger, service-orientated yachting scene in Europe, founded his company Complete Yacht Delivery (CYD) when he discovered what was missing Down Under. Vessel owners were willing to pay for higher levels of crew experience, professionalism, and customer-service, but had nowhere to turn.

Finn sails with the belief that even small vessels and their owners deserve the same five-star service that clients in the super-yacht industry expect. And, after more than ten years at sea, he has connections with professional sailors all over the world, giving him a network of commercially qualified and highly experienced crew. Finn personally vets new crew members to insure they meet CYD’s high standards, and to tailor each delivery with the relevant skills and experience needed for the vessel and the expected (but not always encountered) conditions. On this delivery, apart from Finn and myself, are Dylan Kuipersmith, a commercial skipper and offshore-engineer, and Ross Smith, vessel owner and a sailing veteran with ten Melbourne-to-Devonport races under his belt.

Four hours in Eden and we are refuelled, have repaired our engine a second time and are ready to depart. Beyond the harbour entrance, the southerly has raised three-meter seas, but the worst of the system has already passed on its march north. We beat into the weather, Dylan and I laughing and shivering on deck as we are enveloped again and again by freezing white-water. Cape Howe, and the notorious Bass Strait, lie in wait beyond the horizon. I am relieved of the watch and fall asleep to the lift and dive of the vessel, and by the time I wake we have rounded Cape Howe and the seas are on our beam, the steep, cliff-like waves subdued to a long, rolling swell. Dawn rises over the Bass Strait, and we welcome a brief window of calm.

Deliveries are long, repetitive hours, interspersed with moments of intense excitement. With the sea and wind swinging slowly onto our stern, we make eight knots across The Bass, cheering each time the face of a wave sends our speed into double digits. Albatross glide over us like jet planes. Oil rigs rise like mythical sea creatures on the horizon. The sails billow with cold south-easterly breeze, shooting us across the usually turbulent strait as smoothly as if it were a lake. We wake, watch and sleep, wake, watch and sleep, and on our fourth night at sea, the sun a blaze of orange as it touches the water, Ross suggests we light the barbecue. We don’t realise, but this is our last moment of tranquillity between here and Melbourne.

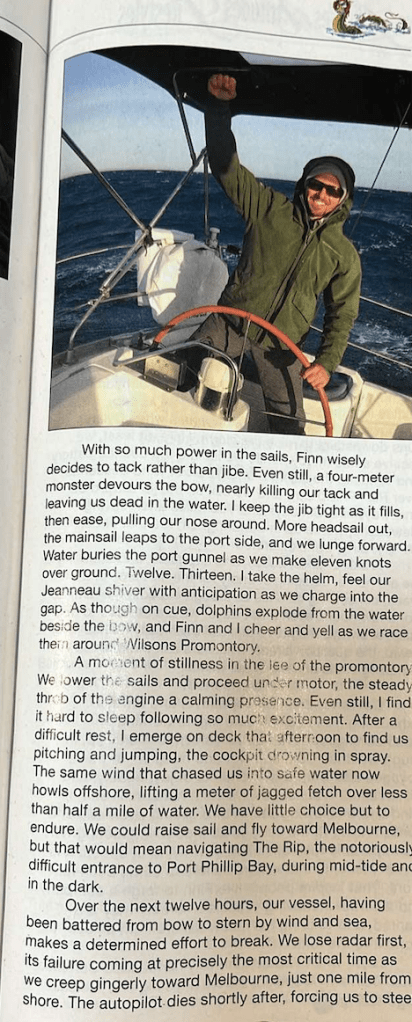

By morning we are nearing Wilsons Promontory, the placid Bass Strait a distant dream. The wind roars a consistent 30 knots, the once calm seas now rearing over our stern. Wilsons Promontory looms like the set of Jurassic Park as we bear down on the tight passage between the headland and the Anser Islands — just Finn and I on deck, steering by hand as we are picked up and hurled forward by the waves. A tanker chases us down, forcing us to hold course until we are less than a mile from the Anser Islands to stay clear of its path through the shipping lane. The sea and wind compress in the narrow gap between mainland and island, flinging us toward the rocks. The wind brushes 40 knots as we prepare to manoeuvre.

With so much power in the sails, Finn wisely decides to tack rather than jibe. Even still, a four-meter monster devours the bow, nearly killing our tack and leaving us dead in the water. I keep the jib tight as it fills, then ease, pulling our nose around. More headsail out, the mainsail leaps to the port side, and we lunge forward. Water buries the port gunnel as we make eleven knots over ground. Twelve. Thirteen. I take the helm, feel our Jeanneau shiver with anticipation as we charge into the gap. As though on cue, dolphins explode from the water beside the bow, and Finn and I cheer and yell as we race them around Wilson’s Promontory.

A moment of stillness in the lee of the promontory. We lower the sails, proceed under motor, the steady throb of the engine a calming presence. Even still, I find it hard to sleep following so much excitement. After a difficult rest, I emerge on deck that afternoon to find us pitching and jumping, the cockpit drowning in spray. The same wind that chased us into safe water now howls offshore, lifting a meter of jagged fetch over less than half a mile of water. We have little choice but to endure. We could raise sail and fly toward Melbourne, but that would mean navigating The Rip, the notoriously difficult entrance to Port Phillip Bay, during mid-tide and in the dark.

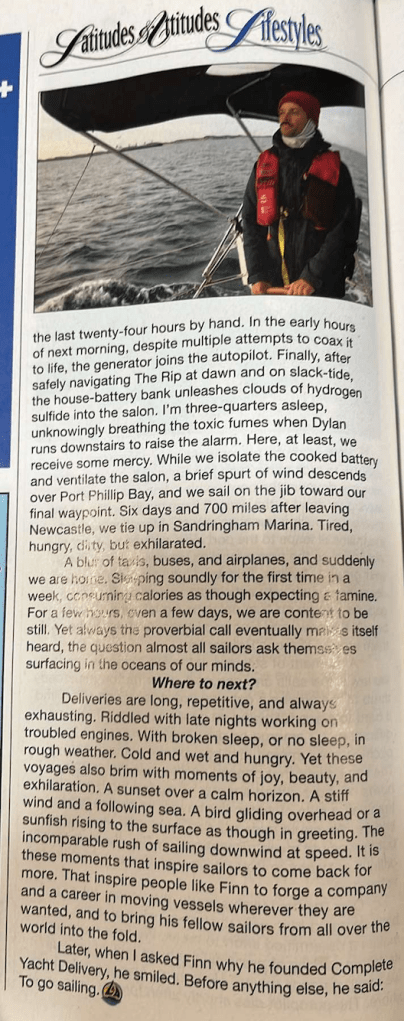

Over the next twelve hours, our vessel, having been battered from bow to stern by wind and sea, makes a determined effort to break. We lose radar first, its failure coming at precisely the most critical time as we creep gingerly toward Melbourne, just one mile from shore. The autopilot dies shortly after, forcing us to steer the last twenty-four hours by hand. In the early hours of next morning, despite multiple attempts to coax it to life, the generator joins the autopilot. Finally, after safely navigating The Rip at dawn and on slack-tide, the house-battery bank unleashes clouds of hydrogen sulphide into the saloon. I’m three-quarters asleep, unknowingly breathing the toxic fumes when Dylan runs downstairs to raise the alarm. Here, at least, we receive some mercy. While we isolate the cooked battery and ventilate the saloon, a brief spurt of wind descends over Port Phillip Bay, and we sail on the jib toward our final waypoint. Six days and 700 miles after leaving Newcastle, we tie up in Sandringham Marina. Tired, hungry, dirty, but exhilarated.

A blur of taxis, buses, and aeroplanes, and suddenly we are home. Sleeping soundly for the first time in a week, consuming calories as though expecting a famine. For a few hours, even a few days, we are content to be still. Yet always the proverbial call eventually makes itself heard, the question almost all sailors ask themselves surfacing in the oceans of our minds.

Where to next?

Deliveries are long, repetitive, and always exhausting. Riddled with late nights working on troubled engines. With broken sleep, or no sleep, in rough weather. With cold and wet and hunger. Yet these voyages also brim with moments of joy, beauty, and exhilaration. A sunset over a calm horizon. A stiff wind and a following sea. A bird gliding overhead or a sunfish rising to the surface as though in greeting. The incomparable rush of sailing downwind at speed. It is these moments that inspire sailors to come back for more. That inspire people like Finn to forge a company and a career in moving vessels wherever they are wanted, and to bring his fellow sailors from all over the world into the fold. Later, when I asked Finn why he founded Complete Yacht Delivery, he smiled. Before anything else, he said: to go sailing.